Deerhunter's Halcyon Digest is one of the most celebrated indie records of the early 2010s, and often considered the creative peak of the band. If you have only a cursory knowledge of the album, you most likely would be familiar with one of its more popular tracks - perhaps the short-and-strummy "Revival," the psychedelic swirl of "Desire Lines," or the tributary closer "He Would Have Laughed." However, when Deerhunter performed on Late Show with David Letterman in February of 2011, none of these songs were featured. Instead, the band opted to perform their upcoming single, "Memory Boy," which was set for a Record Store Day release that coming April and would be the second off of Halcyon Digest. The end result was glorious.

Facts For Whatever

Popular Posts

-

Deerhunter's Halcyon Digest is one of the most celebrated indie records of the early 2010s, and often considered the creative peak of th...

-

Rating: 8.6/10 FIFA is one of the biggest annual video game releases, and one I thoroughly enjoy. Today I will be talking about the pros ...

-

Before the #1 spot on the album of the year countdown, it's time to take a look at some of the records that just barely missed the cut. ...

Subscribe!

Monday, January 26, 2026

Deerhunter - "Memory Boy" (Live on Letterman, 2011)

Tuesday, May 28, 2024

Top Ten Albums That Defined My College Experience

This weekend, I made my first return to Brown University's campus since graduating for my five-year reunion. Reunions are funny in that they are in a way a reversal of college itself: college is all about looking ahead and building a path to the future you see for yourself, but reunions are for catching up on where adulthood has taken everybody and reminiscing on years gone by. While revisiting old haunts like the Blue Room and Thayer Street and, of course, WBRU, I was flooded with memories not only of friends, but of the music that accompanied my final years in academia. This, combined with the reminder (and shame) provided by my visit that I haven't written in quite a while, has spurred me to whip up a list of the ten albums that most prominently defined my college experience. These aren't necessarily the ten albums I enjoyed most during my time at Brown - though they're all fantastic in my book - but rather the ones that I most associate with that time, ones that connect deeply with where I was at those points in my life. I would also love to see your own lists, so please feel free to share which albums tell your college stories too.

10. Girlpool - Powerplant (2017)

Before diving completely off the deep end into her correlating obsessions with AI and Elon Musk, Grimes put out Art Angels, her innovative magnum opus that seemed to foretell a future of weirdo art-pop crossing into the mainstream. It's an electric and eccentric record, marked by highlights covering ground all the way from a friendship falling apart ("Flesh Without Blood") to deforestation ("Butterfly") to Al Pacino as a genderfluid time-traveling vampire ("Kill V. Maim"), drawing from elements of pop-punk, hyperpop, and heavy metal.

According to my Last.fm statistics, this is my most-played album of all time, and by a wide margin. Over half of those plays came in its initial release year, 2017, which tracks well with my memories of spinning it daily throughout the final few weeks of my sophomore year. DAMN. was perhaps my most highly-anticipated record, coming off the back of 2015's masterpiece To Pimp a Butterfly and 2016's compelling Untitled Unmastered. TPAB was the last "big" album of my high school days, and remains my all-time favorite record. Untitled Unmastered and some of Kendrick's other 2016 appearances - particularly his spot on Danny Brown's "Really Doe," Travis Scott's "Goosebumps," and Beyoncé's "Freedom," along with another I'll mention further down this list - only served to whet my appetite for a proper follow-up to TPAB.

So far on this list, I've tried to explain how these albums might have characteristics that appeal to college students at-large, justifying their inclusion. With Every Open Eye, however, it's a more explicitly personal connection. Two weeks after its September 2015 release, I was gifted this album on vinyl for my 19th birthday by new friends I had just met upon starting school. It was a special moment for me, one that let me know that these new friendships were the real deal, and would last beyond our four years on campus together.

Kanye West is obviously an extremely controversial figure who has said and done many horrible things. In fact, I personally have not listened to this Kanye record or any other one in several years - the stink of his rampant misogyny, anti-semitism, and Trumpism lingers too heavily to not be a distraction.

Michelle Zauner may be an indie headliner with a successful memoir and corresponding film on the way nowadays, but that wasn't always the case. Before having her full-fledged breakout via her 2020 album Jubilee and 2021 book Crying in H Mart, Zauner had already put out several records under the Japanese Breakfast moniker, one of which was 2016's Psychopomp. I discovered this album one afternoon in one of Brown's various libraries, camped out in a nook procrastinating on an essay that needed to get done. Centered around the passing of her mother two years prior, Psychopomp explores a wide range of emotions through 25 minutes of indie-pop perfection. The mournful lyrics of "In Heaven" are smothered in blissful synthesizers; "Heft" mentions "spending nights by hospital beds" over a cheerily-strummed guitar riff. The album also looks at relationships, with "Everybody Wants to Love You" and "Jane Cum" each use wildly contrasting instrumental moods to pair with lyrics examining sexuality.

Monday, April 22, 2019

Jamie Vardy: From Carbon Fiber Technician to Golden Boot Contender

The Leicester City squad sat in the home side locker room at the King Power Stadium on a bright morning in September 2015. The players were in good spirits, still buoyant after securing the club’s first win since returning to the Premier League with a victory over Stoke the previous weekend. Still, a sense of caution lingered in the air: Manchester United were not a team you took lightly, after all. Team manager Nigel Pearson, an imposing man who rarely smiled, stands 6’1”, and boasts a widow’s peak unparalleled within British sports, walked in and posted the starting lineup for that day’s match. The players quickly huddled around, eager to see if they’d be taking part. Pearson had opted for an aggressive approach, including three forwards in his starting 11, including the last name on the team sheet: number 9, Jamie Vardy. Laser-focused as always, Vardy simply nodded upon seeing that he’d been given his first-ever start in the Premier League at age 27, never showing so much as a grin. A goal, two assists, and two drawn penalties later, he would lead his team to one of the most exciting and surprising come-from-behind upsets in Premier League history.

The path Vardy followed on his way to that incredible day is one of the most unlikely and inspiring rags-to-riches stories in the history of sport. Born in Sheffield, England in early 1987, Vardy never knew his biological father, who left home shortly after impregnating Vardy’s mother; as a result, he took his stepfather’s last name. His looks and personality reflected his working-class background: a sinewy figure with buggy eyes and short, spiky brown hair, Vardy has always been known for his resounding toughness on and off the field (for better or worse). As a teenager, he joined the youth academy system of Sheffield Wednesday, the club he’d grown up supporting, but was released by the club at just age 15. Vardy was so discouraged by his failure that he nearly quit playing soccer for good: “That was the lowest moment for me,” he told The Guardian last year. Eventually, however, Vardy refused to give up on his dream, and he began playing for the youth side of semi-professional club Stocksbridge Park Steels. He spent four years in the development academy before finally making the first team squad in 2007. At this time, Vardy made a measly £30 a week, and he split his time between soccer and working in a factory making medical splints. He also had a brush-up with the law while at Stocksbridge: after being arrested for assault (which he insists was simply him defending a friend), he played for months while wearing an ankle bracelet, and he often had to leave matches early in order to be home in time for his court-mandated curfew.

Vardy impressed many with his prolific goal scoring for Stocksbridge, and in 2010 Halifax Town spent a miniscule £800 to bring the then-23-year-old to the club. At this point, he decided to focus full-time on his soccer career, risking a steady income in order to pursue his dream. In his one season with the club, Vardy knocked in 27 goals and earned another move up the ladder of English soccer, this time landing at Fleetwood Town for a reported £150,000 – almost 200 times as much as his transfer to Halifax had cost. His new team played in the fifth division, one step below the professional tier. With Fleetwood, he scored 31 goals in 34 league matches, an exceptional rate for a player at any level.

In addition to his beyond impressive goal tallies, Vardy received praise for his particular playing style. Possessing excellent natural speed and acceleration, at any moment he could burst beyond opposing center-backs and latch onto a ball played through a gap in the defense. He could also receive the ball short and dribble through defenders if necessary. Once he worked his way into an opening behind the defense, Vardy’s precise shooting practically guaranteed a goal. His time in the lower leagues gave Vardy a toughness and physicality to his game that many top-level players lacked, especially fellow strikers. Despite standing at an unremarkable 5’10”, he jumped quite well and fought hard to win headers in the air. Mentally, Vardy displayed the kind of determination and work ethic that managers cherish. Moreover, his immense stamina enabled him to hustle for the full 90 minutes of a match without wearing out. All in all, it made for a formidable striker, and Vardy was proving to be one with his goal scoring. He’d been overlooked by clubs so long due to a combination of his size and pure bad luck, a mistake that dozens of scouts will now be cursing themselves over.

At this point, Vardy was grabbing the attention of the coaches and scouts throughout much of England that had ignored him for so long previously. He had carried Fleetwood Town into the fourth division of English soccer – the bottom tier of the professional Football League - for the first time in the club’s history. Vardy was now a professional for the first time in his career, and it was about to get even more exciting for him. Fleetwood received several offers for Vardy’s services, and it eventually accepted an astounding offer of £1 million pounds from Leicester City in 2012, at that point the most ever paid for a non-League player. Now 25 – not old by any means, but still notable considering most players sign professional contracts upon turning 18 if not earlier - Vardy prepared for his first season in professional-level soccer.

The move signaled a massive leap for Vardy: at the time, Leicester competed in the Football League Championship, the second division in England and just one gradation underneath the Premier League – the height of English soccer and arguably the most prestigious and lucrative league in the world. The top two clubs at the end of each Championship season automatically gained promotion to the Premier League, while the teams finishing in places third through sixth competed in a playoff for the coveted third promotion slot. Leicester City were a fairly significant and successful club in English soccer as well, only spending one season outside the nation’s top two divisions, though they’d never won a top-flight title. In the season prior to signing Vardy, the club had finished in a respectable ninth place in the Championship, missing out on a promotion-playoff berth by just a few wins. Not only had Vardy earned a move to a more stable and esteemed club, but he was also reasonably close to achieving every English soccer player’s dream: playing in the Premier League.

However, Vardy struggled to adapt to the new level of competition the Championship posed right away, and he failed to make a huge impression in his first season with Leicester. During the campaign, he managed just four goals in 26 appearances – a drastic decline from his nearly even goal-game ratio from seasons past – and even received taunts from Leicester fans over social media. He was so discouraged that, for the first time since being cut by his boyhood club Sheffield Wednesday at age 15, Vardy considered quitting the game altogether. Fortunately for both the Foxes and Vardy, however, manager Nigel Pearson’s reassurances convinced him to stick around. “I had a few chats with the gaffer and they constantly told me I was good enough and they believed in me and stuck by me,” Vardy said. “I am glad to be showing the faith they showed in me on the pitch.”

Despite Vardy’s shortcomings during his Leicester debut campaign, his teammates hoisted the club all the way to sixth place and a spot in the playoff to gain promotion to the Premier League. It had required a goal in added time in the last match of the regular season to secure a victory and thus a spot in the playoff. Once there, they faced third-place finishers Watford in a two-match playoff, with whichever team that scores more across the pair of games advancing to the playoff final at Wembley Stadium. Leicester snatched a 1-0 victory in the home leg, in which Vardy was an unused substitute, meaning they needed a draw or a win to reach the winner-take-all final.

Vardy was once again on the bench for the away trip to Watford, where he witnessed one of the most dramatic conclusions to a promotion playoff in English soccer history. After 20 minutes the teams had exchanged goals, leaving Leicester on pace for a 2-1 aggregate victory. Shortly after halftime, however, Watford’s Matej Vydra scored his second goal of the match. Now 2-2 on aggregate, the game seemed headed to extra time until Leicester winger Anthony Knockaert drew a penalty in the sixth minute of stoppage time; a goal would send Leicester through to Wembley. Knockaert took the penalty himself, but both his spot-kick and the rebound were saved by Watford goalkeeper Almunia. Watford then stormed down the field in a counter attack, crossed the ball into the box, and scored the playoff-winning goal as Troy Deeney lashed the ball into the net. Leicester had narrowly missed out on a golden opportunity to reach the Premier League.

This devastating loss seemed to only motivate the Leicester City squad to push on for promotion next season, Jamie Vardy included. He earned a starting birth in 34 league matches, scoring 14 goals and nabbing another four assists. Leicester finished first in the division by a comfortable nine-point margin, with a 17-point gap between them and the playoff places. After 10 years, Leicester had finally returned to the Premier League. Like any promoted club, they approached their new top-flight status with both excitement and trepidation; though the promotion opened up plenty of opportunities for the club, retaining one’s position in the league as a former Championship side – which requires avoiding finishing in the bottom three - proves difficult each and every year. In the summer that preceded the 2014/2015 season, the club purchased a handful of new players to aid their survival battle. Included among them was £8 million striker Leonardo Ulloa, who looked poised to cut into Vardy’s playtime. As Leicester embarked on their first season back in the Premier League, Vardy indeed seemed to be losing out on playtime: he had to wait until the club’s third match for his first career Premier League appearance, coming on as a sub for the final 20 minutes against Arsenal but unable to tilt the 1-1 match in his side’s favor. Still, in just over two seasons, he’d gone from a non-league player to leading the frontline against Arsenal in the Premier League.

After sending him in as a substitute once more against Stoke, Pearson handed Vardy his first Premier League start against Manchester United. The game started disastrously for Leicester; within 16 minutes, United lead 2-0 and seemed poised to only pile on the misery for Leicester. But then, Vardy got going on what turned out as a match-winning and career-altering performance. Immediately after the second United goal, Vardy pounced on a long pass from kickoff, dribbled into the attacking corner, and whipped in a powerful cross for Leonardo Ulloa to head home. United scored again to take a 3-1 lead just before the hour mark, but Vardy again helped bring Leicester back within one goal: after tenaciously knocking United defender Rafael off the ball, he drew a foul in the box to win a penalty. Teammate David Nugent scored from the spot to make it 3-2. Just two minutes later, Vardy created his third goal of the match, knocking down a driven pass into the path of midfielder Esteban Cambiasso, who smashed the ball into the net to equalize.

With momentum now on their side, the Leicester players pushed optimistically for a winning goal, and Vardy came up with one in the 79th minute. Displaying his trademark speed and clinical finishing, Vardy took a pass from Richie De Laet into the open field, broke away from the defense, and placed the ball past United goalie David De Gea to put Leicester up 4-3. Vardy stormed towards the corner flag and celebrated with his teammates and the club’s supporters; he had his first Premier League goal, and it had given Leicester a lead against the mighty Manchester United. Incredibly, Vardy still had more to contribute to the match, winning yet another penalty after breaking away once again, with Ulloa scoring the kick to make the score 5-3 in Leicester’s favor. After that match, everybody knew who Jamie Vardy was: the man who’d gone from a non-league semi-professional to almost single-handedly dismantling Manchester United.

Though now a cult hero among Leicester fans and Cinderella-story lovers everywhere, Vardy’s appearances throughout the rest of his club’s season were a bit scattered. His next goal didn’t come until March, and the team as a whole struggled; after 29 out of 38 matches, they sat at the bottom of the league with just 19 points. Just when it looked like the Championship was beckoning, Leicester went on an astonishing run of form. Match-winning goals from Vardy against West Bromwich Albion and Burnley (the former coming very late in the game) helped bring the Foxes up to 14th place and secure a spot in the Premier League for the next season. Vardy’s performances impressed English national team manager Roy Hodgson so much that he granted Vardy his first match appearances for the national side, adding yet another landmark to the striker’s inspirational career trajectory.

As they primed for their 2015-2016 sophomore season in the top flight since returning, doubt once again overshadowed Vardy and his teammates. Pearson lost his job despite the previous season’s late heroics due to a broken relationship with the club’s owners. The firing came shortly after a sex-tape featuring three young Leicester players – one of which was Pearson’s son – leaked online. Pearson took much of the blame for failing to control the behavior of his players, who were heard in the tape making racist remarks to Thai prostitutes, which naturally offended the club’s Thai owners. The board replaced Pearson with former Chelsea and Juventus boss Claudio Ranieri, whose most recent job had been coaching Greece’s national side, only to be fired after losing to the lowly Faroe Islands. On top of everything, key midfielder Esteban Cambiasso left the club, moving to Greek club Olympiakos after declining a contract offer from Leicester. Many experts tipped Leicester as major relegation candidates, and nobody gave them a shot of challenging the league’s top teams. Of course, Jamie Vardy has always been one to defy expectations.

New manager Ranieri set up a Leicester side suited perfectly for Vardy’s play-style: their tactics centered around fighting for the ball, hassling opponents, constantly sprinting throughout the pitch, and breaking on the counter-attack. Paired with new arrival Shinji Okazaki at striker, Vardy flourished under his new manager and started knocking in goals left and right. He scored Leicester’s first goal in a 4-2 win over Sunderland to open the season. A few weeks later, he scored against Bournemouth; goals versus Aston Villa and Stoke City soon followed. A pair of goals over Arsenal and another against Norwich extended his scoring streak to five straight Premier League matches.

Leicester now occupied fourth position in the league, enough to qualify for the European-wide Champions League, though this early in the season, unexpected teams often start impressively before fizzling out. Shockingly, however, Leicester and Vardy kept improving: after returning from two matches with the England team (coming on as a sub in one and starting the other), Vardy scored twice to help his side tie Southampton. Winning goals against Crystal Palace, West Brom, and Watford – the team that had denied the Foxes promotion two years prior – took his tally to 12 for the season, and he was just one more match away from tying the record for most consecutive games with a goal in Premier League history. Leicester were now equal on points with league leaders Manchester City and Arsenal, and pundits finally began taking them seriously. Fans finally recognized Vardy as one of the league’s hottest players, and his reputation skyrocketed among the media. Vardy scored in his next match, a 3-0 victory over Newcastle, to tie Ruud Van Nistelrooy’s goal-scoring streak record and give Leicester sole possession of first place.

For the city of Leicester, their home club’s magnificent run in the premier league has been an inspiring and unifying event like no other. The city’s economy is heavily based in production, much like Vardy’s hometown of Sheffield. Less than have of its residents identify as “white British,” and is one of England’s major landing destinations for immigrants. “We’re like a salad bowl. We live side by side. We don’t live together,” said club supporter Riaz Khan, before offering a little more hope for a more unified community: “When Leicester wins [the league], it will unify the entire the city.” Supporters’ chants such as “Vardy’s having a party!” show just how much Vardy has been a part in reigniting passion for the club and togetherness among Leicester citizens.

Leicester’s next opponent was one with special significance already to Vardy: Manchester United. Van Nistelrooy had set his record with United, and now Vardy aimed to break it against them. He didn’t have to wait long; with less than 25 minutes gone, Vardy jumped on a pass from Christian Fuchs to give Leicester a 1-0 lead, and to give himself a place in the Premier League record books. Being the team player that he is, however, Vardy’s post-game comments focused more on how he wished the team had held on for the win (the match ended 1-1) than on his own personal glory. “[I’m] obviously delighted that I’ve got a goal to take me past Van Nistelrooy, but the boys, I think, are a bit disappointed in the way that we conceded the goal. Who knows?” he said. “On another day, it could’ve been three points.”

Vardy didn’t score in the next match, ending his streak at 11 consecutive games with a goal, but Leicester still won thanks to a Riyad Mahrez hat-trick. Through the Christmastime period which many analysts thought would knock them, Leicester held firm, losing only one of their five December matches and beating the likes of Everton and defending champions Chelsea. As the calendar turned to 2016, it was the other top clubs that began to fall away, and to everyone’s surprise Leicester emerged from the pack as the most consistent title challenger; after comprehensively beating Manchester City 3-1 on the road on February 6th, odds makers now listed Leicester as the favorites to win the league. In the meantime, Vardy scored goals for England against both Germany and Holland, the former a result of a tricky and incredibly bold back-heel flick that beat Manuel Neuer, universally regarded as the best goalkeeper in the sport.

As weeks went by, Leicester kept winning, and it eventually became clear that the only team with a chance of stopping them now was another unlikely (albeit not nearly as shocking) table-topper, Tottenham Hotspur. But Leicester’s consistent victories meant there were few opportunities for Tottenham to make up any ground. However, a red card for diving in a 2-2 and his subsequent verbal abuse of the referee draw versus West Ham (in which Leicester claimed a draw with a last-minute penalty kick by Leonardo Ulloa) resulted in Vardy being suspended for two crucial matches in April, with only four games left in the season. If Leicester won both, they would be guaranteed the title, meaning that the man responsible for so much of their success might not even be allowed on the field to celebrate its culmination. Now, it was up to the rest of Leicester’s squad to carry the club to the title.

Of course, Vardy was not the only one contributing to Leicester’s success, and plenty of talented players were still available in Vardy’s mandatory absence. Due to remarkable consistency and a fortunate lack of injuries, the same group of players made up the match-day squad for the entire season with little variation. There was former French 2nd division player Riyad Mahrez, the fleet-footed Algerian winger who was renowned for his ability to trip up defenders with his tricky dribbles and astounding shooting skills. Central midfielder N’Golo Kante, also coming to Leicester from the French leagues, seemed to cover every blade of grass as he raced around the pitch game after game, making tackles and interceptions as he constantly hassled opponents. Right back Danny Simpson and midfielder Danny Drinkwater were both former Manchester United youth prospects who had been cast off after being deemed not good enough for the club. The defense was anchored by Germany’s Robert Huth and Jamaica’s Wes Morgan, both tactically adept and physically powerful center backs. Morgan was also the club captain. Sitting behind the defense was goalkeeper Kasper Schmeichel, a talented keeper whose father Peter stood in net for Manchester United for almost a decade and is widely regarded as one of the best goalies to ever play the game.

After a Vardy-less 4-0 win over Swansea, Leicester could clinch the championship with a win against Manchester United at their home fortress, Old Trafford. Vardy watched on as his teammates battled in a hard-fought match, but an early United goal from Anthony Martial limited them to a 1-1 draw, the Leicester goal coming from captain Morgan’s header. Though they hadn’t clinched the title, the point gained from the tie meant that Tottenham needed to beat Chelsea the next day in order to prevent Leicester from winning the league with two games to spare. Vardy hosted a viewing party at his home for his fellow teammates to watch the match, though the mood was far from cheery as Tottenham took a 2-1 lead late into the game. But in the 83rd minute, Chelsea winger Eden Hazard completed a mazy run with a curled finish into the top-right corner of the net, leaving Spurs goalie Hugo Lloris helpless to keep his team in the title hunt. Tottenham failed to reclaim the lead, and Leicester were officially crowned champions of the Premier League.

Television networks broadcasted scenes of Leicester fans that had congregated in pubs across the city erupting with joy. Vardy and his teammates joined in, as defender Christian Fuchs uploaded a video of the team celebrating wildly at Vardy’s home to Twitter. Fans poured into the city center, a party-like atmosphere consuming the entire city throughout the whole night. The celebration continued at the club’s home match the following weekend, as Andrea Bocelli sang to a packed King Power Stadium before Leicester beat Everton 3-1, courtesy of a pair of goals from Jamie Vardy, and lifted the trophy in the post-game festivities. After the match, a reporter asked Vardy how Leicester had been able to pull it off. Standing with a Premier League champion’s medal around his neck, Vardy credited towards his teammates and manager: “It’s that togetherness we’ve got. We’re all like brothers.” Reportedly over 100,000 fans showed up to the title parade through the streets of Leicester a week later.

Vardy’s personal accomplishments went heralded as well. He finished joint-second in the league’s top scorer’s charts with 24 goals, one behind Tottenham rival and England teammate Harry Kane and level with £38 million Argentine striker Sergio Aguero. Vardy was named the Footballer of the Year by the Football Writer’s Association, as well as the Premier League Player of the Season. Even more, he’s not only on the England squad for the Euros this summer, but is widely expected to be a regular in the starting lineup throughout the tournament. All of these accolades show just how Vardy has become emblematic of the unpredictability and upward mobility of soccer not just in England but throughout much of the world. Nobody could ever have expected a 25-year-old semi-professional player to lead the Premier League in goals and to take Leicester, despite the odds, to the top of English football.

In the midst of all the excitement and hubbub surrounding him and his team this season, Vardy opened up a training academy for non-league players, where they can receive high-quality coaching and get scouted by top-level clubs. “I know there are players out there in a similar position to where I was, that just need an opportunity,” he explained. “I’ve thought for some time that something could be done about it… we decided to set up V9 [the camp] to unearth talent and give those players a shot – hopefully at earning professional contracts but also to learn and understand what it takes to be a professional at the highest level.” If all goes according to plan, he may just end up discovering the next Jamie Vardy.

Squashed

Men’s Basketball Falls to Princeton at Home, Stay Bottom of the Ivy League

Thursday, June 16, 2016

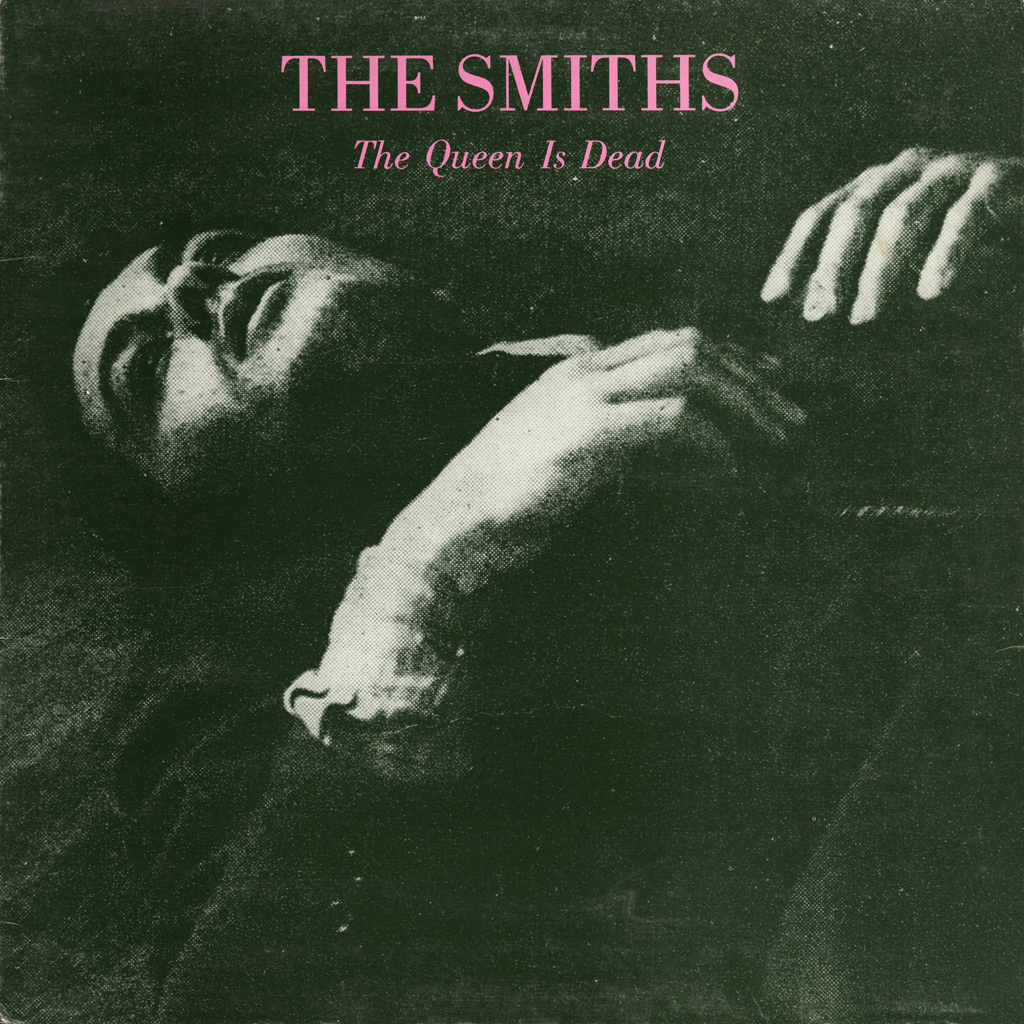

Some Albums Are Bigger Than Others: A Look at "The Queen Is Dead" Thirty Years Later

Rating: 9.8/10

Thirty years ago today, legendary Manchester band The Smiths released The Queen Is Dead, their greatest album and one of the most revered records in music history. The Smiths were already making waves in the British alternative scene of the 1980's with their strong first two LP's - The Smiths and Meat is Murder - and non-album singles like "How Soon Is Now?" and "Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want." But on The Queen Is Dead, The Smiths hit another gear: Johnny Marr's riffs were more addictive than they'd ever been, Andy Rourke's bass lines became even more indispensable, and Morrissey delivered the best vocal performances of his career. Never before or since did the group put together a more complete album, and today it stands as one of greatest albums of the decade if not of all time.

The Queen Is Dead begins with its title track, one of the most ferocious pieces of music The Smiths ever recored. A sample from the 1962 movie The L-Shaped Room is cut off by a wail of feedback and a thunderous drum pattern before the band launches into a six-minute psychedelic escapade. Like the best songs by The Smiths, "The Queen Is Dead" features lyrics that veer from bitingly sarcastic to emotionally direct and devastating. Here, he starts with the former, alluding to the title of the album and further demonstrating his disdain for the British Monarchy: "Her very Lowness with her head in a sling / I'm truly sorry but that sounds like a wonderful thing." Here, we get our first glimpse of the macabre theme that permeates so much of The Smiths' music, but The Queen Is Dead in particular. Later, he offers a bit less dark humor and a bit more vulnerability, repeating "Life is very long when you're lonely."

The Queen Is Dead also features the strongest one-two punch of gloom The Smiths ever recorded, in the form of consecutive tracks "I Know It's Over" and "Never Had No One Ever." The former is one of the most relatable and moving break-up songs ever written. Though Morrissey recognizes via the title that his relationship is no more, he's still unable to detach himself from the other person emotionally: "And I know it's over / I still cling / I don't know where else to go." "Never Had No One Ever" (double negative be damned) explores an even sadder character, as Morrissey fills the shoes not of someone who can't get over an ex, but somebody who's never even had an ex.

Of course, The Smiths are just as good at being light as they are at being heavy. The bouncy "Frankly, Mr. Shankly" remains perhaps the funniest moment of the group's discography, with lines like "Frankly, Mr. Shankly, since you asked / You are a flatulent pain in the arse." (In true Morrissey fashion, the singer then proceeds to almost immediately request, "give us your money!") "Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others" is laughable, though not in the way Morrissey probably intended; while he probably wanted us to snicker at his lyric on its own merit, the humor comes from the contrast between the song's mesmerizing instrumentals and ridiculous, mediocre lyrics. Even "Vicar In a Tutu," the album's only real step down in quality, offers up chuckle-inducing imagery. Earlier this week, Simon Price wrote a piece for The Quietus in which he suggested that these moments of levity detract from The Queen Is Dead's emotional impact and overall quality. As a counterpoint, I would argue that they offer much-needed breaks from the melancholy, and make the album feel more genuine and more human.

What makes The Queen Is Dead stand apart from other Smiths records and in truth from pretty much all but a handful of other albums in general are the absolutely blissful, brilliantly-worked instrumentals. Rarely will you find a track so effortlessly buoyant as "The Boy With the Thorn In His Side," or guitar-bass interplay as captivating as that on "Bigmouth Strikes Again." The false fade at the beginning of "Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others" is a unique stroke of genius that will never be replicated to the same effect, and the guitar work that follow is one of Marr's greatest achievements.

"There Is A Light That Never Goes Out" wouldn't feel nearly as magical without those soaring strings.

_cover_art.jpg)